During one of my trips back to visit my parents in Malaysia, I went to get a facial, since it was cheaper there than in the United States. The beautician was a nice chatty lady from Melaka, where my father and relatives hail from. During the session, I started to ask her about what she remembered about Nyonya cuisine while she was growing up there. She listed a bunch of dishes that I was very familiar with, until she started to describe a certain salad dish. At this point, I stopped her and asked her to give me a more detailed description of its ingredients. When she finished describing the dish, I realized then that my family had not eaten this salad since Mamah passed away nearly twenty-five years before. I was so excited about finding a lost culinary treasure that I asked my mother to go the market the next morning to purchase the ingredients, and that night, we recreated the dish.

While preparing this dish, I could not believe that after twenty-five years I still remembered how the dish should taste, the flavor memories still at the tip of my tongue as I adjusted the amount of salt, sugar, chili paste, and lime juice that make up the dish’s seasoning. During dinner, my parents, my aunt, and I were very quiet as we ate the salad. A sense of comfort and reminiscence came upon us, and our eyes looked slightly glazed. At that point, I knew that my grandmother was present then and there through that particular dish—it was a very touching moment for all of us.

An enquiry by me about this dish on a Baba-Nyonya Facebook group produced a lot of responses and some interesting information. First, it confirmed that the dish’s Baba Melayu name was correct, as I had not been sure of its veracity, and that there is a northern Penang version called Kerabu Timun, as well as other versions in the Kelantan Peranakan and the Malacca Portuguese communities. I also learned that my version was missing a key component, pounded dried shrimp or dried brine shrimp (gerago), that brings the dish’s umami factor to another level—for this, I’m grateful for the help of social media and the group Peranakan members for guiding me with this “lost” recipe. Some commented that they grew up eating a version made with boiled pork skin, and my father even remembers a version made with chicken intestine. And finally, many posted that they had not eaten this dish in a long time, including quite a few that wrote that they last ate it when their mothers were alive; a lady remarked she had not tasted the dish for nearly 70 years. This last revelation stirred up in me the same sadness and sense of nostalgia when I rediscovered this recipe years ago as I realize how quickly certain dishes like this one could easily be forgotten or not transmitted to future generations.

This dish is basically a salad incorporating cooked chicken gizzards and pork with fresh cucumber and a full-flavored spicy sauce, made fragrant by slivers of torch ginger flower (bunga kantan). This flower is essential in imparting its citrus-like and uniquely aromatic quality to the dish. However, it is very difficult to find its fresh form outside of Southeast Asia (hence the commissioned photos by a Malaysian friend)—do not use the dry form as it is too fibrous for the dish (you may omit it and still produce a tasty dish). As with the other salad-like dishes, this is not served as a separate course but rather as part of the whole meal. Do not mix the sauce with the meat and cucumber in advance otherwise the cucumber will be soft and the dish too soggy. Hopefully, the flavors in this dish will tickle your palate and touch your heart like it did when my family revived and saved it from possible extinction.

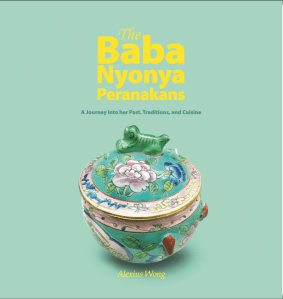

Recipe from The Baba Nyonya Peranakans book

Serves 4

Preparation time: 45 minutes

4 chicken gizzards

250 grams (½ pound) pork belly, skin removed with a bit of fat left on

1 medium cucumber

2 tablespoons dried shrimp, soaked in water for 10 minutes, drained, and pounded or processor chopped not too finely

4 small (40 grams/1½ ounces) shallots, peeled and cut into fine rings

2 tablespoons sambal belacan ; or 3 or Finger Hot red chilipeppers, seeded and stemmed (or 1½ tablespoons chili paste or sambal oelek), plus 6 grams/½ teaspoon belacan (shrimp paste), crushed together into a fine paste

5 tablespoons lime juice (10 limau kasturi or 3 limes)

½ head bunga kantan (torch ginger flower), sliced diagonally, very finely

½ teaspoon salt

1½ teaspoons sugar

- Put the chicken gizzards and pork belly into a pot on medium heat, and pour in enough water to cover. Simmer covered for 30 minutes—you may proceed with the next step and prepping the other ingredients. When cooked, remove and slice the pork thinly into slices 2-by-3 centimeters (¾-by-1 inch). Slice the gizzards into very thin long pieces.

- Peel the cucumber and halve it lengthwise. Remove the seeds using a tablespoon. Slice the cucumber diagonally into ½ centimeter- (¼-inch-) thick pieces.

- In a bowl, combine all the ingredients and mix well. Taste and adjust the salt and sugar levels. Serve immediately.

The hardcopy and e-book of The Baba Nyonya Peranakans book (1st image) and Edible Memories e-cookbook (2nd image) are available – more information on the Homepage.